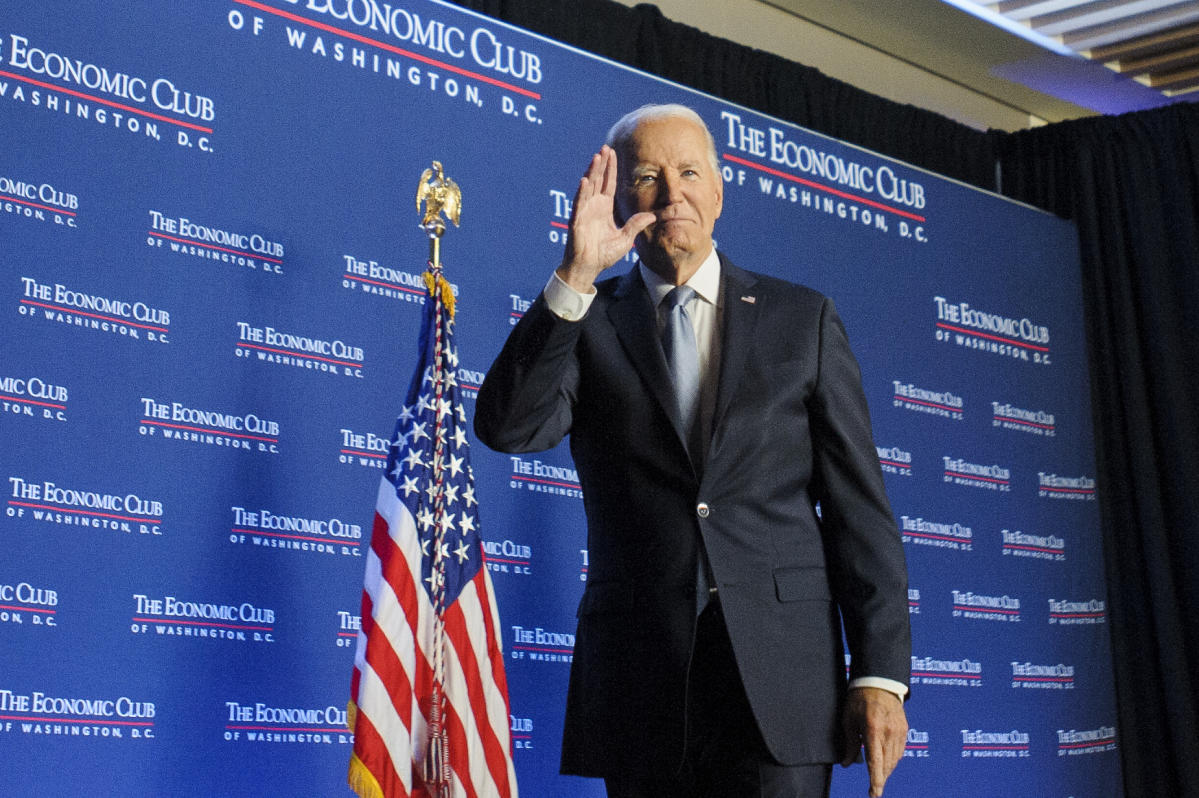

In one of his final moments on the world stage, President Joe Biden will attempt to burnish his legacy and bolster Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign this week. But his most important foreign policy goal appears to be slipping away.

Biden will make his final appearance this week before the United Nations General Assembly — a group of world leaders nervously eyeing November’s U.S. election — but his farewell address could be overshadowed by rising violence in the Middle East. And as Israel’s battle with Hezbollah across Lebanon’s borders has stoked growing fears of a broader regional war, it also jeopardizes what three administration officials say has become Biden’s top priority for his remaining time in office: a ceasefire in Gaza. All were granted anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly about private conversations.

Ceasefire negotiations in the war between Israel and Hamas had already stalled before hundreds of pagers and walkie-talkies exploded in Lebanon and Syria last week, killing more than 20 people and wounding more than 3,000 in a bold move targeting Hezbollah militants. That led to an exchange of rockets between Israel and Lebanon and raised fears of an extended conflict.

“President Biden has done everything he can to prevent a regional war in the Middle East. He has stood by Israel, and his deterrence has helped prevent an escalation,” said Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.), who sits on the Foreign Relations Committee and has perhaps the closest relationship with Biden of any senator. “But the dynamic between Israel and Hezbollah has become increasingly fractious, and I am concerned.”

“No one has worked harder for a hostage and ceasefire deal than Joe Biden and his senior advisers,” Coons continued. “But I’m not optimistic that we’re going to see a deal anytime soon.”

Biden plans to use his time in New York to make a forceful case that he has made good on his promise of a renewed American engagement abroad over the past three and a half years, following President Donald Trump’s tumultuous and confrontational time in office. But the rising risk of war in the Middle East, combined with the ongoing war in Ukraine and lingering questions about the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, threatens to tarnish his record and help Trump prove that the world has become more chaotic since he left the White House in 2021.

The centerpiece of Biden’s time at the United Nations will be his speech on Tuesday, in which he is expected to emphasize the need for alliances, urge the protection of democracy and call for peace in the world’s trouble spots. He will also meet with a number of world leaders.

Biden entered his presidency with the most foreign policy experience of any president in decades, and, in many ways, his internationalist view of the world has been rewarded with a series of victories. Biden vowed that “America is back” and rebuilt America’s alliances; he helped countries stand up to Russia’s Vladimir Putin; and he and his national security team have managed to reopen key channels of communication with the world’s rising superpower, China.

Rapidly changing global events have exposed the limits of Biden’s power. And while foreign policy traditionally scores low with voters, the White House — and Harris’ campaign — must now manage their fallout in the heat of a competitive campaign.

This is especially true in the Middle East.

Even as tens of thousands of Israelis have taken to the streets to protest Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s handling of the war, the Israeli leader has consistently said he prioritizes security — and the elimination of Hamas — over retrieving remaining hostages. The operation against Hezbollah has only added to the commotion.

“Biden was right to support Israel’s right to self-defense after October 7, but 11 months of American cajoling and pleading have achieved little,” said Richard Haass, former president of the Council on Foreign Relations. “The war continues, the hostages remain hostages, and there is no plan for what comes next in Gaza. Biden has not been willing to engage this Israeli government to the extent necessary and move toward a more independent American policy.”

Biden has told his national security team that reaching a ceasefire deal is his top priority for the rest of his term, the three officials said. He believes it would cement his legacy in two ways: First, it would give him credit as a peacemaker; and second, it could ease Harris’ path to victory.

Two major issues are preventing the U.S. from moving the deal forward, one of the officials said. Israel has demanded that it keep a limited number of troops along the Philadelphia Corridor, a demilitarized zone along the Egyptian border. Hamas has rejected that proposal, saying Israel must withdraw all its troops from the area. There are also significant differences between Israel and Hamas over the number and timing of the exchange of Palestinian prisoners for hostages.

Biden’s most trusted advisers — CIA Director William Burns, Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan — have made a deal their main focus. The president recently convened a Situation Room meeting with his national security officials and urged them to ignore recent setbacks and continue working with both parties and outside negotiators to find a deal.

“Keep fucking trying,” Biden recently ended a meeting with the officials, according to one of the participants.

Biden administration officials plan to resume talks on a Gaza ceasefire this week, but there is little expectation that an agreement can be reached anytime soon, the three officials said. There is deep skepticism that Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar or Netanayhu are eager to make a deal, and the Israeli leader’s latest demands have renewed suspicions within the White House that he wants to prolong the war to maintain his own grip on power, and potentially help Trump.

Harris is not expected to attend this week’s meetings in New York, though she is expected to meet with some world leaders in Washington. Still, the global landscape she inherits will be shaped by these and other efforts by the Biden administration in its final three months in office.

The challenges Harris takes over as Democratic standard-bearer will test her national security credentials just as the campaign enters its final stretch. And for the vice president — who has so far stood firmly behind Biden on policy but distanced herself with her rhetoric — the lack of progress has created a political dilemma.

Harris has repeatedly reaffirmed her belief in Israel’s right to defend itself and has not proposed restricting arms shipments to Jerusalem. But her team is aware of the anger in the Democratic base over the humanitarian crisis and the concern that it could depress turnout among young voters, progressives and Arab-American voters, particularly in a state like Michigan where the odds of success depend.

She has sought to increase Palestinian suffering and has secretly pushed the administration to increase pressure on Netanyahu to strike a deal, two of the officials said. But aides acknowledged she risks disappointing activists who want her to explicitly change course and stop sending weapons to Israel that have been used to kill Palestinian civilians.

Biden is no longer seeking re-election and will increasingly focus on foreign affairs in the coming months. His team has eyes on a number of foreign trips before his term ends, including the G20 summit in Brazil and a long-awaited stop in Africa.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine will be a major focus at the United Nations. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy will meet separately with Biden and Harris in Washington later this week and is expected to present them with a plan for victory. In a speech in Kiev last week, he expressed frustration at not receiving approval from the U.S. and U.K. to use long-range weapons, a topic he is certain to raise with the president and vice president.

Biden’s success in building a coalition to help Kiev is seen by his advisers as his greatest foreign policy achievement. But a Trump victory could quickly undo that triumph.

Trump has repeatedly said he would end the conflict in “one day,” marking a radical shift in U.S. policy. While he has not provided specifics, the White House believes Trump would threaten to stop aiding Kiev and demand that Zelensky accept the current battlefield lines — which would give Putin control of a significant portion of Ukraine.

“The fact that Ukraine has not fallen to Russia after all this time is a success, although the future of course remains uncertain,” said Julian Zelizer, a presidential historian at Princeton University. “Everything indicates that Harris would continue the same policy, [and] A Trump defeat would be a blow to the GOP’s non-interventionist movement.”

The Biden administration continues to map out how to spend all $60 billion in aid authorized in the latest congressional supplemental appropriation and has not ruled out making another request for money after the election, the three officials said. In addition, the president could use his drawdown powers to release more supplies if needed, and another trip to Europe to deliver a speech on the need to assist Ukraine is being considered, the officials said.

Biden also made a public effort to forge alliances amid an increasingly aggressive China this weekend, when he hosted other Quad leaders — India, Japan, Australia — at his Delaware home and announced policies to bolster security in the Indo-Pacific.

“President Biden’s foreign policy has been driven by convictions,” said Mark Hannah, a senior fellow at the Institute for Global Affairs. “Some of those convictions have run counter to conventional wisdom inside the Beltway and have required real political courage to translate into policy.”

“But some other beliefs seem outdated,” Hannah said, “remnants of the geopolitical environment in which the president spent most of his political career.”

Erin Banco contributed to this report.