Under a veil of secrecy, the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office leaned on a confessed mass shooter for years, building cases using information he’d collected from jail in ways that experts called improper, and likely, unconstitutional. His involvement has already threatened at least two murder convictions.

Prosecutors and police had William “Little Bill” Brown ask around about suspects and rumored crimes, the Miami Herald learned from jailhouse phone calls. Brown kept an eye on a key state’s witness. In manufactured jailhouse meetups, he obtained confessions and gathered intel on the defense strategy of accused criminals, and gave it to law enforcement.

He owed them. Prosecutors had given Brown the plea deal of a lifetime — 25 years for two murders, including one involving a middle-schooler, when he was potentially facing the death penalty. He also got a pass from prosecution after he secretly confessed to involvement in at least four other murders, including two teens killed in one of Miami’s worst mass shootings. The public, and victims’ family members, never knew.

For more than 10 years, prosecutors have kept Brown protected at a local jail, preventing him from being sent off to prison and offering him a chance at an early release as they leaned on him for help, according to records reviewed by the Herald.

“I think the whole thing looks extremely unseemly,” said criminal law expert Kenneth Nunn, a professor emeritus at the University of Florida’s law school. “And it is beneath representatives of the state to use their authority and power in a way like that, to coerce an individual to do things that they know are unethical and perhaps violate due process.”

Prosecutors’ clandestine relationship with Brown, pieced together in telephone recordings, internal emails and sworn statements reviewed by the Herald, comes to light now for the first time, as the office of Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle faces mounting claims of misconduct. Their use of the informant contributed to a judge’s decision this year to throw two prosecutors off a capital murder case, and is at the center of a push for a new trial in the murder of an eighth-grade girl.

At the center of the controversy is Michael Von Zamft, a prolific if controversial prosecutor thrown off the death penalty case of Miami gangster Corey Smith in March for — in the words of the judge — the planned “manipulation” of witness testimony to give the state an unfair edge in court.

Although he denied wrongdoing, Von Zamft’s tenure at the State Attorney’s Office ended that day when he abruptly resigned, finalizing his planned retirement amid the barrage of criticism over his conduct. Assistant State Attorney Stephen Mitchell was also booted from the Smith case for going along with Von Zamft’s “prosecutorial philosophy of winning at all costs,” according to the judge’s order.

After Von Zamft’s departure, Mitchell took over as Brown’s contact at the State Attorney’s Office. Mitchell continues to lead the state attorney’s gang unit. He is still prosecuting the case involving the murder of the middle-schooler, which a defense attorney seeks to overthrow, in part based on Brown’s involvement.

It’s unclear how many cases have relied on information supplied by Brown over the years. In the handful of phone calls reviewed by the Herald, law enforcement made extensive requests that went beyond the bounds of what was required by the plea agreement — which one defense attorney called a “deal with the devil” — brokered by Von Zamft in 2014.

The recorded conversations indicate that prosecutors and a detective wanted Brown to tap his connections for information about crimes to which he had no personal involvement or knowledge — essentially deputizing him as an informal agent of the state, according to court records.

A telephone recording reviewed by the Herald indicates that Von Zamft and Mitchell planned to have Brown meet up with another inmate they knew was trying to communicate with Smith ahead of his resentencing. The inmate had gleaned valuable information on Smith’s defense strategy, Brown told prosecutors on the call, promising to “pick his brain” for details during the planned meet-up.

Encouraging someone to seek out information from people in jail about their cases or alleged crimes could violate the other inmates’ rights to an attorney and due process, as well as the constitutional protection against self-incrimination, according to eight criminal law experts, including five current or former Miami prosecutors.

While prosecutors can build a case using testimony from an inmate who happens to overhear something while in jail, the experts said law enforcement officials cannot direct someone in jail to prompt a confession from another inmate.

“It’s ok to be a listening device; it’s bad to ask questions” in jail, where most people are represented by counsel, said former Miami prosecutor David Weinstein. Asking an informant to gather information from someone on the outside, he said, would be less problematic.

After reviewing the Herald’s findings, Weinstein said what troubled him most was how prosecutors and detectives appeared to be “putting people in places where they’re going to invade the defense camp or where they’re going to be actively soliciting information.”

Von Zamft, Mitchell and Fernandez Rundle declined to be interviewed by the Herald. The Herald requested to interview Brown or his attorney at the Public Defender’s Office, which represents him.

“We have no comment at this time,” Guy David Robinson, the office’s general counsel, responded to the Herald.

The State Attorney’s Office did not answer detailed questions about Brown, saying they can’t comment on the specific situation.

Chief Assistant State Attorney Stephen Talpins said, “We believe deeply in our roles as ministers of justice and expect our prosecutors to do the right things, for the right reasons, in the right way, each and every day.”

“We are very careful to respect defendants’ constitutional rights,” Talpins said. “As a matter of policy, we do not ask inmates to do anything we cannot do ourselves, including questioning other inmates.”

Talpins said the state attorney expects professionalism and fairness from prosecutors, and provides training consistent with the office’s commitment to justice. He said prosecutors are “handicapped” by understaffing and old technology.

“We are doing the best we can, given those limitations. Like everyone else, we can make mistakes,” Talpins said. “When we make those mistakes, we correct them, learn from them, and move forward consistent with our mission to protect our community in the most fair and just manner possible.”

‘We love you, Bill’

Von Zamft and Mitchell treated Brown like an old pal — and an honorary member of their team, in a 2023 telephone call reviewed by the Herald.

“What’s up with you, my friend?” Von Zamft said warmly to the confessed multi-murderer who called one day from jail on a recorded line. They bantered about a former member of Brown’s gang who wouldn’t get the plea deal that he was hoping for.

Brown wasn’t surprised. His former buddy had been “toying around” with the prosecutor — something he knew “Mike” would not appreciate.

“It’s not just me,” Von Zamft said. “Steve Mitchell’s the same way. He’s nastier than I am.”

Mitchell, who was on speakerphone with Von Zamft, laughed at the description. By then, Brown was on a first-name basis with both prosecutors.

Von Zamft asked if Brown had “any connections enough to make calls to find out” more about someone the prosecutors suspected of planning a hit. Brown replied, “I can look into that.”

When Brown told the prosecutors not to trust one of their key witnesses, dubbing him “an asshole,” they gushed, “That’s why we love you, Bill. Because you’re straight up.”

Brown, now 33, was no run-of-the-mill street criminal when he cut a deal with the State Attorney’s Office in 2014.

As the teenage leader of the A&E gang (so-named due to their affection for American Eagle branded clothing), Brown landed in jail in January 2010 indicted for first-degree murder for gunning down a 19-year-old, Bernard “Bear” Moore. Brown told one friend that he shot Moore “like 17 times in the face.” A survivor, who was shot in the back by Brown, identified him as the killer.

Brown’s criminal activity did not stop just because he was behind bars. Then 19 years old, Brown encouraged fellow gang members to keep up the war against a rival gang, he confirmed as part of his plea deal. But when the guys went out to shoot down its leader, they botched the job, shooting eighth-grader Sabrina O’Neil in the head.

Afterward, as they drove away from the crime scene in Brownsville, the gangsters spoke on the telephone with Brown, and he was gleeful, laughing, singing and making gun sounds on the recorded line because he thought they’d taken down his enemies.

“You know you made me happy, boy,” Brown said to one of them.

The senseless murder of O’Neil renewed outrage about gun violence in a community torn by gang fighting. Caught on the taped call, Brown was charged for her murder as well.

Potentially facing the death penalty if convicted in either case, records reviewed by the Herald show Brown began feeding information to law enforcement.

In late 2013, following a string of deadly robberies that left a 10-year-old boy and a 21-year-old man dead, Brown called a Miami police detective to say one of the accused shooters, his childhood friend, was housed in the same jail block while awaiting trial. Brown said he was planning to meet his former buddy the next day to “find out more” about the crime.

Following the meeting, Brown called back to say he had gotten a confession and information on three crimes, which he noted down on a sheet of paper. His public defender passed the note on to law enforcement, and it was ultimately entered into evidence and used by the State Attorney’s Office. (Mitchell and Von Zamft were not handling the case.)

Under oath, Brown testified that he had not prompted the jailhouse confession out of his old friend in 2013 and when asked, he said he was instructed not to ask questions.

But, according to a summary of one call, the detective sent Brown back for more details.

To former Miami prosecutor Melba Pearson, all of Brown’s work for law enforcement appeared to be a “wink, wink, nod, nod” situation.

“Why are you calling him and talking to him and mentioning these people’s names if you didn’t want him to go follow up?” said Pearson, who worked in the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office for 15 years before unsuccessfully running against Fernandez Rundle. “You’re calling him and you’re giving him these names specifically of people that are housed in the same prison as him with the expressed purpose of him doing something.”

Aside from any legal concerns, using an incarcerated person to collect information is fraught, Pearson said, “because the reality is, this particular person has an incentive to make up stories. They have an incentive to lie.” That is especially true, she said, if the deal includes potential incentives like the possibility of a reduced sentence as Brown’s did.

But Von Zamft didn’t think Brown was a liar. In fact, the prosecutor thought Brown was “really f—ing smart,” as he said on one call. In another, he praised Brown for providing accurate information.

“He does well, taking care of himself,” Von Zamft said of Brown on a recorded call. “As long as he continues doing that, I’ll continue to try and help him.”

Confessions of a mass shooter

The day after the police detective confirmed receipt of Brown’s notes on his friend’s 2013 jailhouse confession, the State Attorney’s Office formalized a plea agreement with Brown, the Herald found. Brown got 25 years for the charges pending against him, including the two murders that had carried the possibility of a death sentence.

By then, court records show Von Zamft had evidence that Brown had participated in a third murder — the 2007 killing of Richard Jolly. Brown was just 17. But under the plea agreement, the State Attorney’s Office relinquished its ability to prosecute Brown for that or any other murder he admitted to as part of the deal.

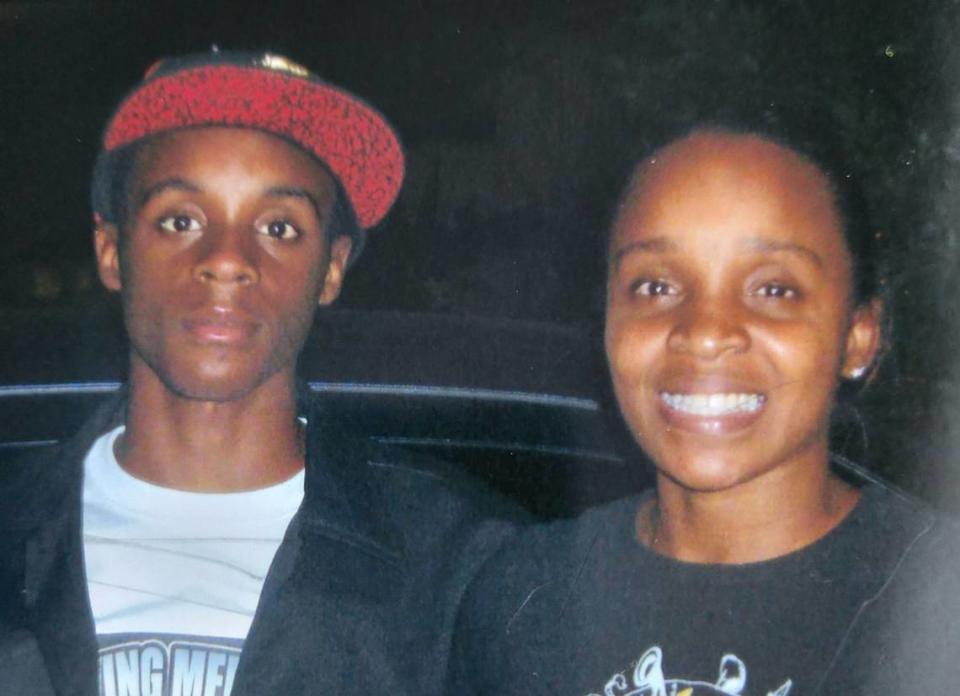

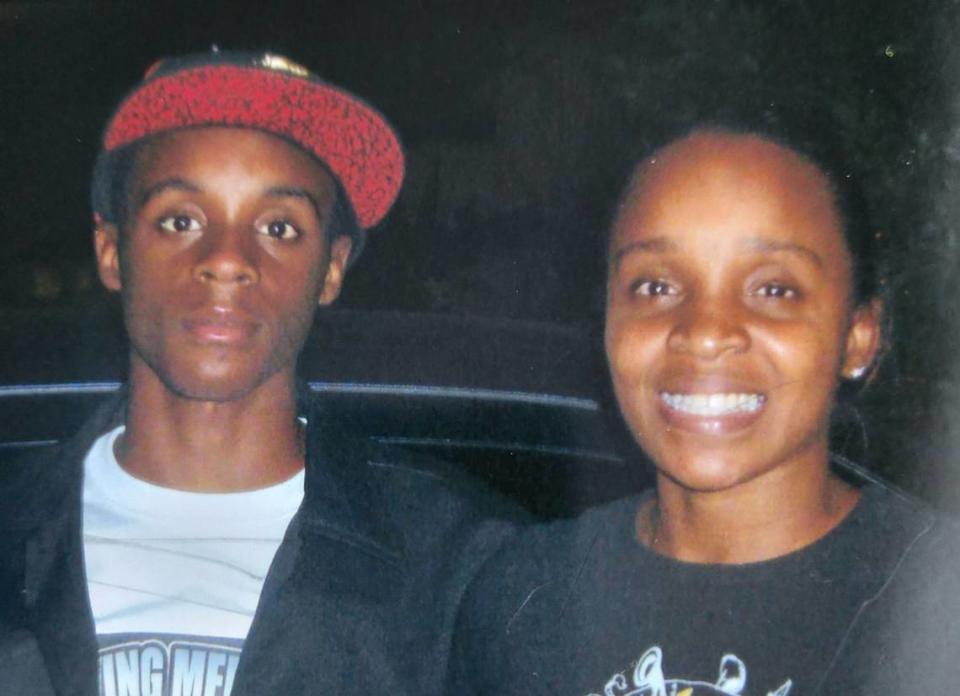

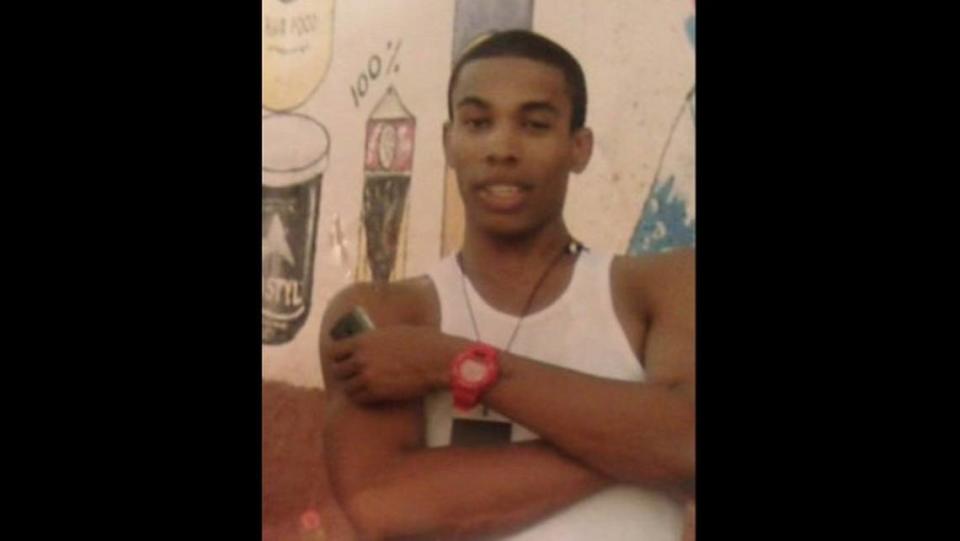

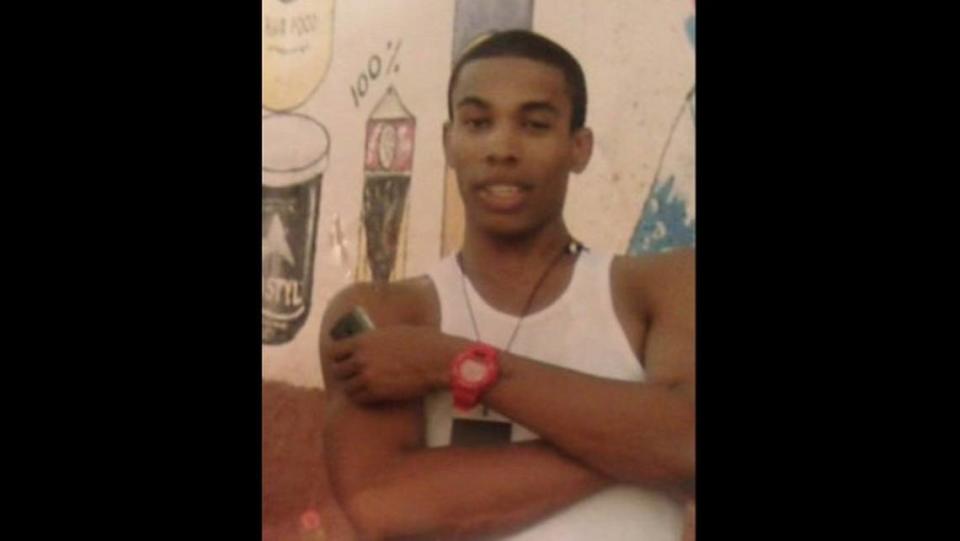

Promised immunity, Brown confessed to what was described at the time as the “worst mass shooting in Miami’s history.” He told prosecutors how, armed with an assault rifle, he and a friend mowed down a group of young people playing dice on the street corner. They shot nine people, killing 18 year-old Derrick Gloster and 16 year-old Brandon Mills. Most of the victims were current or former students at the local high school, Miami Northwestern.

Dubbed the “Liberty City Massacre,” the cold-blooded shooting on Jan. 23, 2009, sparked national outrage. But Brown’s confession and the accompanying immunity deal was kept quiet. Even family members of the victims said they didn’t know.

In 2021, Crime Stoppers re-posted a video about the case soliciting help solving it. In the video, a woman named Tangela Johnson begs her 18-year-old son’s killer to “turn themselves in.”

Johnson said no one ever told her that Brown confessed to the Liberty City shooting. The teen’s father said he wasn’t told, either. Both said they knew Brown was a suspect in their son’s case, but were told there wasn’t enough evidence to charge him. Neither knew anything about Brown’s immunity deal until called by a Herald reporter.

“I don’t understand why would they do this when I told them how important this was to find out who did this to my son,” Johnson said.

The Herald was unable to reach Mills’ family.

Despite the confession and deal preventing Brown’s prosecution, the case remains open at the Miami Police Department, rendering all of the evidence exempt from public viewing. The second shooter was already dead when Brown named him in his confession.

In exchange for immunity, prosecutors and police from multiple departments got Brown’s cooperation in any case that “relates to any criminal activity to which he was a party, or of which he was aware.”

“As a result of this cooperation, no additional charges will be filed except for the charges which are pending at the time of the ratification of this plea agreement,” the agreement reads.

“They made a deal over my son’s life,” said Derrick Gloster, whose teenage son with the same name was killed in the shooting. “I wanted to see the person who did it prosecuted. … That was my only son, with my same name. He was my only son.”

Calls for mistrial

Under his plea agreement, Brown was specifically required to testify against his four friends who carried out the botched drive-by he’d ordered from jail in 2010 that killed the young girl. In exchange, he got no extra time for her death.

Two of Brown’s former pals took 15-year plea deals from Von Zamft and Mitchell, the prosecutors assigned to the case. The others who went to trial got life sentences. One was a shooter. The other, Taji Pearson, drove the car, but a jury found he didn’t wield a weapon.

And now, Pearson’s case seems to be unraveling.

In legal filings, defense attorney Michele Borchew argued prosecutors incentivized both Brown and the other primary witness, and improperly withheld that information from the defense.

Brown was chasing the possibility of a reduced sentence, a hope Von Zamft had dangled in front of him in exchange for his testimony, Borchew alleged in legal pleadings, pointing to an email and recorded calls she obtained only after the sentence was handed to her client.

The other state’s witness, Dwayne Miller, who admitted providing the guns and bandanas for the shooting, was compensated — his mother was given at least $5,000 by police, Borchew found. Jurors who convicted Pearson never had that information, she said. Prosecutors in a recent court filing said they hadn’t known about the payment, which was to help the woman move after she was threatened.

The defense also wasn’t given an email that Dwayne Miller sent in 2022 to Von Zamft, telling him that he didn’t recall what happened all those years ago, and accusing the prosecutors of “trying to make me remember.” Von Zamft then sent a transcript of the lead detective’s testimony to refresh Miller’s memory.

An appeals court agreed with Borchew that important evidence related to Miller’s credibility might have been withheld, and on April 30 ordered the case sent back down to the local trial court.

While the state attorney’s office acknowledged Miller’s email should have been handed over, Mitchell argued Miller’s “credibility had little impact in this case.”

“Again, the recorded jail phone call between the Defendant and William Brown provided overwhelming evidence of the Defendant’s guilt,” Mitchell argued in a response to the motion to overturn the conviction.

The case is ongoing.

Borchew, who wants a new trial for Pearson, told the Herald that the State Attorney’s Office “fosters a culture of winning at all costs.”

“It’s a numbers game that is easy for them to play in a system that does not look at the accused as humans,” she said.

‘Glaring instances of misconduct’

It was due to a fluke of fate, or perhaps her intuition, that Borchew first learned of Brown’s close relationship with the prosecutors on her client’s case.

A hearing in Pearson’s case ended, and Borchew heard the prosecutors — Von Zamft and his co-counsel Mitchell — say they were headed to another hearing. She decided to follow.

Borchew walked into one of the most consequential cases of the year — one that would cast doubt on the prosecutors’ integrity and throw a negative glare on Fernandez Rundle’s office. It was a resentencing hearing for Corey Smith, who was convicted in 2004 for participating in four murders as a member of the John Does gang, named for the toe tags of their victims.

Smith had spent the better part of two decades on and off Death Row.

In court this year, Smith’s attorneys argued that his conviction should be thrown out because they had obtained new evidence in the case indicating prosecutors had incentivized witness testimony. They also argued that the entire State Attorney’s Office should be disqualified from handling Smith’s case for pervasive misconduct spanning decades.

Borchew was intrigued. She sat through every day of the hearings. Cooperating witnesses housed in the nearby jail in the lead up to the 2004 trial described how prosecutors brought them together in the Miami Police Department to make sure their stories lined up. There, they said they were given alcohol, tobacco, and their choice of food, like Popeye’s, Pizza Hut, K.F.C., and even Joe’s Stone Crab, as “sort of a treat.”

While reviewing the case at the police department, the inmates said they also spent time with family and friends – including conjugal visits.

Von Zamft and Mitchell were not the prosecutors on the case at the time witnesses’ testimony was allegedly coordinated at the police department. But, defense attorneys also argued that prosecutors, including Von Zamft and Mitchell, had routinely withheld information important to Smith’s defense throughout the years, and the State Attorney’s Office “insisted on keeping us in the dark at every turn.”

At a hearing on Feb. 28, Smith’s Attorney Craig Whisenhunt said, “we have found time and time again additional instances of profound and persistent misconduct by this office, by Mr. Von Zamft specifically, and by the office in its entirety.”

Whisenhunt argued that “somewhere along the way this State Attorney’s Office lost sight” of its mission to seek the truth above all else, saying Smith’s case “became a personal vendetta, not to seek justice, not to pursue the truth, but at any cost to condemn a man to die because they had decided he was a monster.”

They drove the argument home with a recorded jail call from Aug. 3, 2022, which Miami-Dade Circuit Court Judge Andrea Wolfson later described as a “smoking gun” containing “glaring instances of misconduct or, at the very least, severe recklessness.” On that call, Von Zamft spoke with a witness in the case, an inmate named Latravis Gallashaw, a convicted murderer who had once allegedly plotted to kill a prosecutor.

The two spoke like old friends, discussing witnesses whose testimony they could no longer depend on in the resentencing hearing that would determine whether Smith would face the death sentence for his crimes.

At one point, Von Zamft mentioned finding a way to make one witness “unavailable” if she refused to cooperate.

“You would want to do that?” replied Gallashaw.

That comment could be reasonably understood as a threat to the witness’ life, Wolfson wrote in a March decision, although she noted she did not personally believe that to be Von Zamft’s intent. Even still, she wrote, “it is unsettling to think a member of the bar, a prosecutor, would manipulate the facts of a situation in the case of a witness who is alive, well and competent to testify to satisfy the legal definition of ‘unavailability.’”

Wolfson removed both Von Zamft and Mitchell from Smith’s resentencing, arguing “the prosecutors in this case have lost sight of their responsibility, and justice demands their disqualification.”

She allowed the State Attorney’s Office to retain control of the case but agreed with the defense that “the State’s treatment of discovery in this case has been questionable throughout the litigation process.”

Wolfson has not yet ruled on the motion to vacate the conviction. In her March order, Wolfson said the testimony from witnesses alleging misconduct by various prosecutors in the State Attorney’s Office over the span of the two-decade trial “will be relevant to the Court’s future ruling on the post-conviction motion.”

For Borchew, hearing the recorded jailhouse call was something of an “aha” moment.

While discussing how to “rehabilitate” a witness who had given contradictory testimony in the case, Von Zamft said he was trying to arrange a jail yard meetup between Gallashaw and another inmate he called “Brown” and “Little Bill” — the nickname of the witness in Borchew’s case.

When Brown’s name was uttered, Borchew said Von Zamft shot a glance at her, like he knew she’d recognize it.

Following the hearing, Borchew got a judge’s order for all the taped calls Brown made to the State Attorney’s Office and police detectives from jail.

She began to piece together a surprising scenario — that Von Zamft had kept Brown in the jail to collect information for 10 years now.

Brown, she wrote in a recent filing, is “an informant and agent for the state and the police.”