(Bloomberg) — Of all the solutions for a warming world, “planting more trees” seems pretty obvious.

Most read from Bloomberg

But in New Zealand, which tested this premise by linking incentives for forest development to its emissions trading system, the results were more controversial and less effective than climate advocates had hoped.

Now, after four years of feverish planting, a prominent government watchdog has joined international agencies, industry groups and environmentalists in calling for a radical overhaul, a reform that threatens a turnaround in the fortunes of investors in the recent forestry boom.

“Pine cultivation and permanent forestry are legitimate land uses,” Parliamentary Environment Commissioner Simon Upton wrote in a report on land use change published in Wellington on Wednesday. “But afforestation should not be encouraged by treating it as a cheap way to offset fossil fuel emissions.”

It’s an aggressive challenge to one of the world’s most prominent afforestation campaigns. Ingka Group, the largest global Ikea franchisee and a major investor in New Zealand’s forestry industry, said in an email that Upton’s advice “is significant, and we are closely monitoring any potential impacts,” adding that the long-term obligations in the country are unchanged. . Other forestry investors say the ongoing debates are undermining confidence in the market.

“While uncertainty remains, New Zealand is missing a significant opportunity to expand its forest estate,” said Phil Taylor, director of New Zealand Forestry at Port Blakely, which owns 35,000 hectares of mixed plantations. “It needs to be sorted out.”

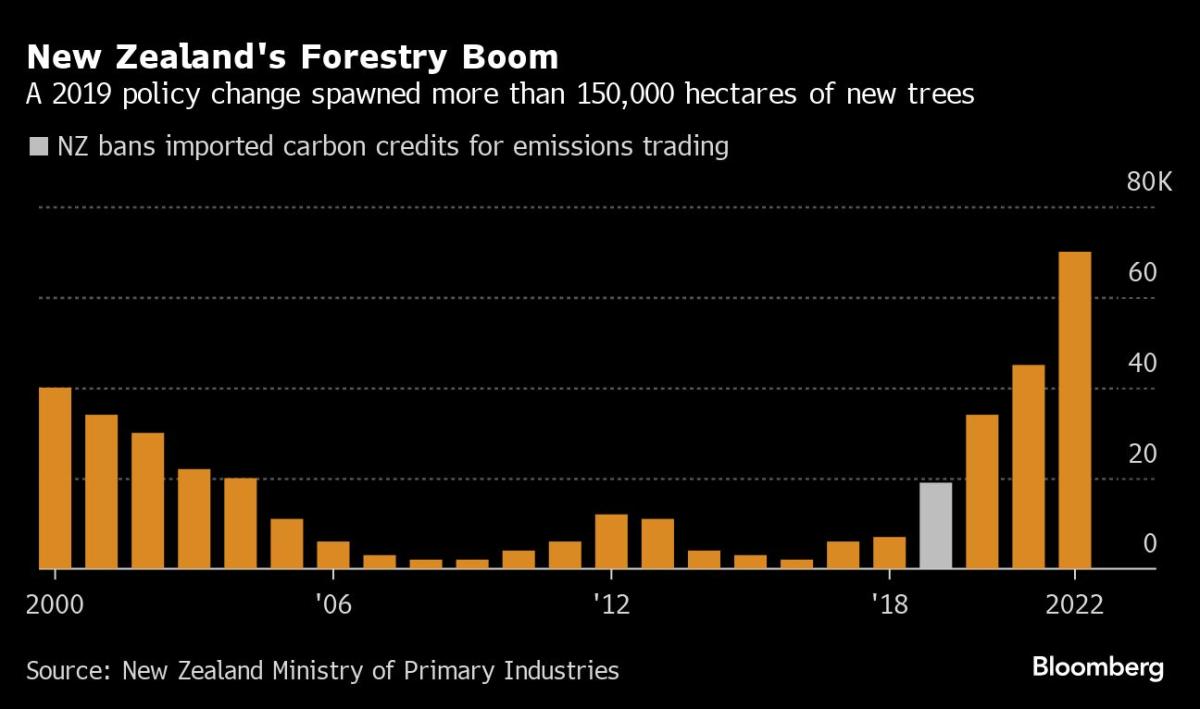

Since 2019, the country has added some 175,000 hectares of forest, almost all fast-growing, carbon-sucking Pinus radiata pine, helping New Zealand make progress towards its 2050 net zero target. But the new growth has damaged the country’s agricultural land country, says the beef and sheep lobby, thereby undermining the meat and dairy industries. Increased forestry waste – the logs, leaves and branches known as “slash” – has more than doubled the damage from the floods caused by last year’s Cyclone Gabrielle.

While these could be valuable trade-offs for significant long-term reductions in carbon emissions, the current system doesn’t really achieve that either, experts say.

Forests absorb a lot of carbon dioxide, but their efficiency decreases over time. To achieve the same environmental impact over decades, “you have to keep planting more and more forests,” says John Saunders, a senior researcher at Lincoln University’s agronomy and economics research unit. “That doesn’t really solve the problem.”

Policy change

The seeds of New Zealand’s recent forestry boom were planted in 2019, when the country’s emissions trading system required companies to use only domestic measures to offset carbon. In practice, it banned companies from purchasing foreign-developed carbon offset products to reduce their carbon footprint.

At the same time, the new rule reinforced an existing and unusual feature of the policy. Companies doing business in New Zealand are allowed to offset 100% of their emissions with credits generated by domestic forest projects. Most countries limit the use of offsets to make more fundamental cuts in carbon emissions.

The combination made forestry more lucrative almost overnight: Not only could trees be harvested for lumber, they could also generate the carbon credits valuable to local businesses. Investors, including Germany’s Munich Re and Japan’s Sumitomo Corp., bought land. Ingka Group has purchased 23 separate forestry areas, although it notes that it does not generate or sell carbon credits.

The land grab also created opportunities for New Zealand farmers, driving up the price of land. The 30-year net present value of land with production forestry and carbon credits is NZ$21,300 per hectare, 144% more than expected yields from sheep and beef, says Julian Ashby, chief insight officer at Beef + Lamb New Zealand, an industry group . .

“The huge additional returns from carbon mean foresters have been able to offer significantly more land,” says Ashby.

Since the beginning of 2021, the country’s foreign investment regulator has approved nearly 150 applications to buy more than 102,000 hectares of land for forestry, of which about two-thirds was agricultural land. The farmers’ lobby has long been an outspoken critic of the aggressive afforestation policy, calling it a threat to beef, dairy, wool and mutton, which make up about 46% of the country’s annual exports.

“The government wanted more trees. The price of land went up so much that farmers could no longer compete,” said Murray Hellewell, who raises sheep and beef on a 640 hectare farm in the South Island. One by one, his neighbors sold it to forestry companies, nearly surrounding Hellewell’s farm with pine trees.

Forest owners, for their part, say farmers’ criticism is short-sighted and that adverse policy changes could impact the NZ$5 billion in annual forestry exports, which are also a major contributor to the country’s GDP.

Investors need confidence in the emissions trading system, says Elizabeth Heeg, head of the New Zealand Forest Owners Association, and reducing the role of forestry offsets would not be good for the country’s climate goals. “There is no sense in the report suggesting that reducing forestry production is a positive way forward,” she said in a statement.

The new government has said it is exploring revisions to the emissions trading system to limit the conversion of productive agricultural land to forestry, although Climate Change Minister Simon Watts said in an email that limiting forestry credits is not on the table. “We recognize concerns about the extent and pace of land use change in rural areas, and the need to balance productive land use,” he said.

Upton’s report offered one solution that could meet the needs of at least some farmers and environmentalists. One problem with current forestry credits is that they are used to offset carbon emissions, mostly from fossil fuels, that linger in the atmosphere forever – which means the forest must also live forever, against the risk of disease, fire, storm. or human behavior.

But biogenic methane, the greenhouse gas emitted by livestock, has a greater warming effect, but for a shorter period of time. From 2030 onwards, farmers will have to pay for those emissions or find a way to offset them. Forestry could be a solution, according to Upton.

“For short-lived gases such as methane, the goal is to reduce emissions to an acceptable flow, rather than eliminating them altogether,” he wrote. Using forests to offset methane emissions “is a more justifiable strategy than using them to offset fossil carbon dioxide.”

Most read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 BloombergLP