One day later launching a spaceship rocket In a dramatic test flight in Texas, SpaceX readied a Falcon Heavy rocket for launch Monday from Florida to send a $5.2 billion NASA probe on a 2.8 billion-mile journey to Jupiter to find out. whether one of its moons harbors a habitable subsurface ocean.

If all goes well, Europa Clipper will enter orbit around Jupiter in April 2030, making 49 short passes by the icy moon Europa, an ice-covered world whose interior is being warmed by the relentless squeeze of Jupiter’s gravity as it swings around the giant. planet in a slightly elliptical orbit.

NASA

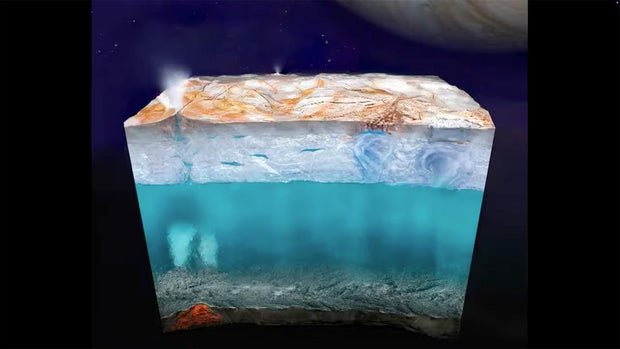

Data from previous missions and long-term studies from Earth indicate that a vast saltwater ocean lurks beneath the moon’s frozen crust, providing a potentially habitable environment. Whether microbial life exists in that ocean is unknown, but the Europa Clipper’s instruments will try to find out if this is at least possible.

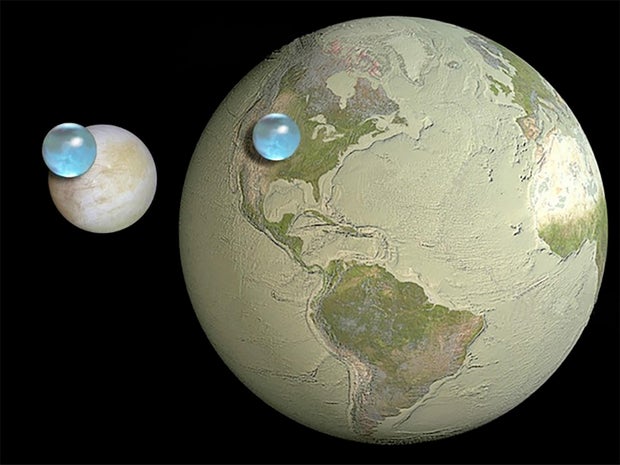

“Europa is an ice-covered moon of Jupiter, about the size of Earth’s moon, but it is believed to have a global subsurface ocean containing more than twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined,” says project scientist Robert Pappalardo.

“We want to determine whether Europa has the potential to support simple life in the deep ocean, beneath the ice cover,” he said. “We want to understand whether Europe has the key ingredients to support life in the ocean, the right chemical elements and an energy source for life.”

NASA originally planned to launch Clipper last week, but mission managers ordered a delay Hurricane Miltonthat swept over Cape Canaveral on Thursday. An additional day flight was ordered to resolve a technical issue and although no details were provided, the rocket was cleared for launch.

The launch from historic pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center was scheduled for 12:06 a.m. EDT on Monday. The triple-core Falcon Heavy, the most powerful operational rocket in SpaceX’s inventory, generates more than 5 million pounds of thrust and will boost the 12,800-pound Europa Clipper to the speed needed to break free from Earth’s gravity .

While SpaceX normally recovers first stage boosters for refurbishment and reuse, all three core boosters and the rocket’s second stage will use all their propellants to accelerate the Clipper to the required departure speed from Earth. As such, recovery in the first phase is not possible.

“Falcon Heavy is giving Europa Clipper everything, sending the spacecraft to the furthest destination we’ve ever sent, meaning the mission requires maximum performance, so we won’t be bringing back the boosters,” said SpaceX President Julianna Scheiman. NASA scientific missions.

“I don’t know about you, but I can’t think of a better mission to sacrifice boosters for a place where we might have a chance to discover life in our own solar system.”

To reach Jupiter, the Clipper will first fly past Mars on March 1, using the red planet’s gravity to increase its speed and bend its trajectory to return the probe to Earth for another gravity flight in December 2026 This will ultimately result in the Clipper being on course for Jupiter.

NASA

If all goes well, the probe will enter orbit around Jupiter on April 11, 2030, using the moon Ganymede’s gravity to slow down before firing the probe’s thrusters for six to seven hours. The first of 49 planned flybys of Europe, some as low as 26 miles above the surface, will begin in early 2031.

The mission is expected to last a minimum of three years, with the possibility of extension depending on the health of the spacecraft.

In either case, the Clipper will end its journey with a kamikaze descent to Jupiter’s moon Ganymede to avoid any chance of a future uncontrolled crash on Europa that could bring terrestrial microbes to the moon and its potentially habitable subsurface environment.

“The spacecraft faces some major challenges,” Pappalardo said. “Jupiter is five times further from the sun than Earth. That means it’s very cold out there and there’s only weak sunlight to power the solar panels. So they’re huge.”

Once deployed, the 15-foot-wide solar panels will extend over 100 feet from end to end – more than the length of a basketball court – with two radar antennas extending up to 55 feet from each array.

Aside from the power requirements, Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field “acts like a giant particle accelerator in Europa,” he said. “A human would receive a lethal dose of radiation within a few minutes to a few hours if exposed to that environment.”

The Clipper is designed to withstand repeated doses of extreme radiation while flying close to Europe, with the flight computer and other particularly sensitive equipment housed in a vault shielded by aluminum-zinc alloy plates.

But engineers were dismayed when they discovered earlier this year that crucial electrical components used in the spacecraft failed at lower than expected radiation levels.

Engineers and managers conducted a major evaluation to determine how this might affect the Clipper and ultimately concluded that the spacecraft could minimize radiation-induced degradation by slightly changing the way the flybys are performed. The only alternative was to delay the launch for several years to replace the suspect components.

Mission scientists were eager to finally launch the long-awaited mission.

“What would be the best outcome? For me it would be to find some kind of oasis, if you will, on Europa, where there is evidence of liquid water not far below the surface, evidence of organic matter on the surface, said Pappalardo. “In the future, NASA might send a lander to dive beneath the surface and literally search for signs of life.”

NASA

As for what kind of life might be possible beneath the moon’s frozen surface: “We’re actually talking about simple, like single-celled organisms,” he said. ‘We do not expect as much energy for life in the European ocean as here on the Earth’s surface.

“So we don’t expect fish and whales and things like that,” he added. “But we are interested in whether Europe can support simple life forms, single-celled organisms?”

The Clipper is equipped with nine state-of-the-art instruments, including narrow and wide-angle visible light cameras that map approximately 90% of Europe’s surface, capturing details down to the size of a car. An infrared camera that looks for warmer areas where water may be closer to the surface or even spray into space.

“The cameras will observe more than 90% of Europe’s surface with a resolution of less than 100 meters per pixel, or 325 feet,” said Cynthia Phillips, project officer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “That’s about the size of a city block.

“The narrow-angle camera will be able to take pictures at a resolution of up to half a meter per pixel, which is about 1.6 feet. And so it will be able to see objects the size of a car on the surface of Europa.”

Two spectrometers will study the surface chemistry and composition of the moon’s ultra-thin atmosphere, looking for signs of water plumes and other ocean-driven features. Two magnetometers will probe the subsurface ocean by studying electrical currents induced by Jupiter’s magnetic field.

An ice-penetrating radar will “see” up to 30 kilometers beneath the ice crust to look for pockets of water in the ice and help scientists understand how the ice and water interact with the supposed ocean.

“These signals will penetrate into the subsurface, where they could potentially reflect off a liquid water layer, such as a lake in the icy shell, or perhaps even penetrate completely, depending on how thick the ice layer is at the surface and other factors, such as the structure and composition of it,” Phillips said.

“The radar could penetrate as deep as 30 kilometers. That’s about 30 kilometers below the surface.”

Two other instruments will study gas and dust particles on the surface and floating in the atmosphere to analyze their chemical composition. Finally, scientists will measure small changes in the probe’s trajectory, allowing them to gather details about Europa’s internal structure.

“We know our Earth as an ocean world, but Europa is representative of a new class of ocean worlds, icy worlds in the far outer Solar System where saltwater oceans could exist beneath their icy surfaces,” Pappalardo said. ‘In fact, icy ocean worlds could be the most common habitat for life not just in our solar system, but in the entire universe.

“Europa Clipper will explore such a world in depth for the first time. … We are on the threshold of a new era of exploration. We have been working on this mission for so long. We are going to learn how common or rare habitable icy worlds are could be.”