After California’s $20 minimum wage for fast-food workers went into effect in April, some economists expected affected restaurants to cut jobs. So what actually happened? Not only were they adding workers, but they were doing so at a faster rate than fast food restaurants across the country — or at least that was the claim of one study paper by two labor economists from the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, Davis.

If you actually read it, you will notice that the results celebrated in the press release and repeated by the media are not in the newspaper. In fact, little attention has been paid to the effect of the minimum wage increase on fast-food employment in California. It offers no figures and no models. There is no evidence that fast food jobs increased after the law was introduced.

The paper’s findings were trumpeted as evidence that government-mandated wage increases have no detrimental effect and that we should raise the minimum wage higher and in more places.

Employment is only shown towards the end of the 25-page survey. There you will find a graph that comes closest to an argument in the article. It shows employment in full-service and fast-food restaurants in California, shown by the red line, and in the US, shown by the blue line, from 2023 to 2024.

(Adani Samat)

The authors argue that the data are prone to sampling error, and come to the ambiguous finding that “we detect no evidence of an adverse effect on employment.” But the paper’s summary ignored the warning in the fine print, boldly stating: “We find that the policy… has not reduced employment.” The accompanying one press releasewhich is probably all journalists have read states that “contrary to restaurant groups’ fears, the wage increase has not led to job losses.”

But the solid red line on the graph clearly shows that fast food employment in California is increasing more slowly than the solid blue line showing national fast food employment, which is the opposite of the authors’ claim. If anything, this data shows that the minimum wage increase has reduced fast-food jobs in California.

(Adani Samat)

But it is still difficult to make an accurate estimate based on the way the graph is presented. That’s why I looked up the numbers, which tell a different story than the authors claim. Although the article was published in September, the chart ends in July 2024, when California fast-food employment rose 1.85 percent since March 2024, while the national fast-food sector rose 3.22 percent.

(Adani Samat)

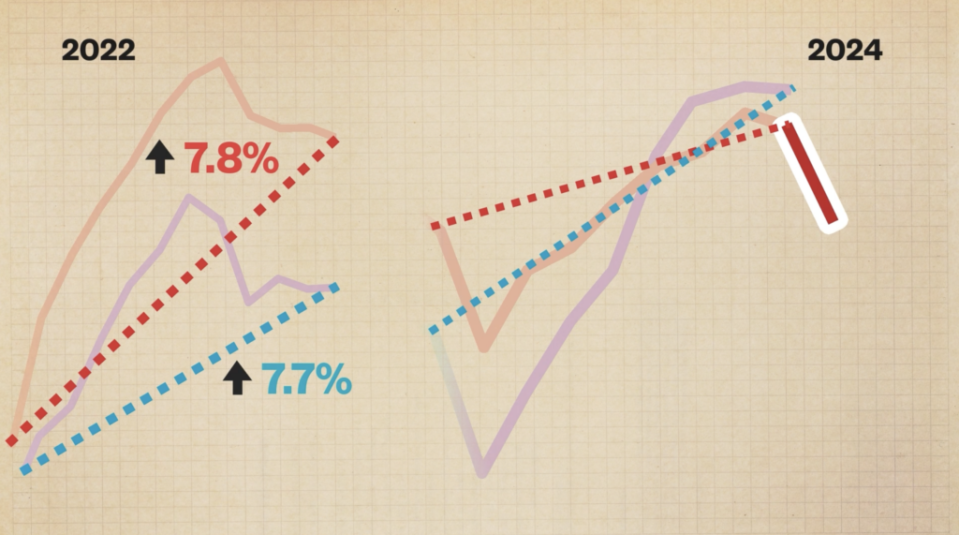

This is a sign that the minimum wage is having a negative impact. In 2021 and 2022, fast-food employment grew at nearly the same pace in both the national and California fast-food sectors: 7.7 percent over the two years nationally, and 7.8 percent in California. But in 2024, growth slowed dramatically in California, and employment began to decline after July.

(Adani Samat)

The slowdown started a few months before the law went into effect, but that’s exactly what you’d expect since the law was signed by the governor in September 2023 and management’s decisions to close, open or open their restaurants names would have been taken pending the law being implemented.

(Adani Samat)

But even with my version of the map there is a major problem. The data used to draw the red solid line doesn’t just represent fast-food restaurants covered by the law; they also include casual restaurants exempt from the law, such as buffets, Panera Breads, smaller fast food chains, donut and snack shops, grocery store concessions, and most delis. If fast food restaurants were negatively impacted by the law, we would expect some of the exempt establishments to expand to capture their market share and thus create jobs. By combining data from exempt establishments, which were likely growing, with data from restaurants affected by the minimum wage increase, the negative effect of the law can be hidden in the data.

Looking at raw aggregates tells us little. But California has the information from employers’ job reports that could resolve the issue. Each quarter, California employers file a series of reports with the state detailing each employee’s hours and payment by Social Security number. The state knows everyone who worked for a fast-food company covered by the law, and what their wages and hours were before and after the law went into effect.

Another study on the same topic,”Early Impact of California’s $20 Fast Food Minimum Wage” by Daniel Schneider, Kristen Harknett and Kevin Bruey, sponsored by Harvard’s Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, used data from semi-annual surveys of retail workers in Western states. In this case, the researchers focused only on fast-food workers . according to law, with the exception of exempt restaurants.

Immediately after the new fast food law went into effect, fast food workers in California lost an average of two work hours per week as a result of the law, the newspaper said. But the authors used misleading language to report this result, because their margin of error for the estimate meant that the actual change could vary from an average loss of five hours to an average gain of one hour. “We can reject large reductions in working hours,” the study reports. “We find no significant effects of the minimum wage increase on usual hours.”

Both statements are misleading. The authors may dismiss that the average loss in hours was greater than five per week, but five hours – or even two – is a big loss. The estimated loss of two hours per week is economically significant for the low-wage workers, but not statistically significant by conventional criteria (meaning it could be the result of random noise). The correct wording is “we have failed to find statistically significant evidence” of wage losses, not “we find no significant effects.” Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Another shortcoming is that the study only covered fast-food workers who kept their jobs after the law took effect, excluding missing workers who were laid off and workers at restaurants that closed. And the respondents were self-selected: people who respond to Facebook and Instagram ads to take a survey for a chance to win a $500 gift card. This isn’t a random selection of people, and they don’t always answer the questions seriously or honest. This isn’t a sample that anyone would expect to find solid evidence of anywhere, so not finding it doesn’t mean much one way or another.

Finally, the study only concerns the first months after the law came into effect. Some changes may take months or years to occur.

The main objection to high minimum wages is not their effect on aggregate employment, prices, or profits; it’s the fear that they’re cutting off the bottom rungs of the economic ladder for low-skilled workers. Instead of being able to work for low wages while improving job skills and making connections for advancement, they are forced into the underground cash economy or public assistance. Therefore, studies of these laws should focus on the impact on these low-skilled workers, rather than on economic aggregates.

The right way to study the impact of the $20 minimum wage is to look at what happened to fast food workers who earned less than that amount before April 1, 2024. How many employees had their wages increased and their hours maintained? How many people have lost their jobs or hours, and what did they do next? Were low-skilled workers able to compete for the new vacancies after the introduction of the law?

If minimum wage increases were medicine, governments would have to conduct trials and then monitor the adverse effects. That’s what happened in Seattle when it raised the minimum wage in 2014. The city called for proposals to examine the impact on actual workers who earn below the legal minimum. The Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington was the only volunteer. His researchers found that the law did not lead to an increase in layoffs among workers who had previously earned below the minimum wage, but did reduce their hours by an average of 7 percent. This was partly offset by a 3 percent increase in hourly wages for the hours they did work. On balance, the law cost these workers an average of $888 per year.

That amount is significant in itself, but it is important to remember that it only takes into account the short-term effects. As mentioned above, some layoffs and reductions will happen immediately, but others – such as more businesses closing and fewer openings, or automation and other changes that reduce employment – could take years. Another point is that workers who benefited from higher wages were those most likely to have risen from minimum wages to the middle class even without a mandatory wage increase, while workers who lost much more than $888 per year are more likely. are the ones forever blocked from economic progress. In fact, the paper found that the workers who net benefited were the most experienced and highest-paid workers in the group – earning more than the old minimum, but less than the new – while the less experienced workers who earned the old minimum or came close, lost significantly more than the average.

Seattle lawmakers must have been dissatisfied with these findings because they cut funding for the Evans School and reached out to the same group at UC Berkeley that did the California minimum wage study to produce its own biased analysis, i.e. rushed outside a week before the Evans study was made public. Ultimately, Seattle raised the minimum wage again.

These studies are not about seeking truth with statistics; their goal is to score political points, with little regard for the low-skilled workers whose lives are directly affected.

The post No, California’s $20 Minimum Wage for Fast Food Workers Didn’t Create Jobs appeared first on Reason.com.