With the presidential elections less than six months away, Joe Biden and Donald Trump will soon unveil their platforms and begin rallying voters around their agendas for 2025 and beyond. And while K-12 education typically spends little time in the national spotlight, the campaign will bring much more clarity to the candidates’ positions on controversial issues like school choice, standardized testing and civil rights protections for students.

But research shows that both men might be wise to play their cards close to the vest. According to an article published this spring, presidents who weighed in on education policy debates between 2009 and 2021 — such as COVID-era school closures or the adoption of Common Core — tended to polarize the public much more then stimulate. Only if they endorse proposals that directly contradict the traditional position of their parties will they succeed in generating general public support, the authors write.

The findings seem to argue for caution in an election year, especially when views on national politics have varied as widely and consistently as they have in election history. They also raise challenging questions about whether federal leadership in K-12 schools can be viable in the absence of the bipartisan consensus that largely favored school reform in the 1990s and 2000s. If not, state-level actors such as governors and legislators may remain in the driver’s seat for the foreseeable future.

Get stories like this straight to your inbox. Sign up for the 74 newsletter

The difference in positive evaluations of teachers unions is about the same as the partisan gap on legal abortion under all circumstances.

David Houston, George Mason University

David Houston, a political scientist at George Mason University and lead author of the paper, said the educational divide between Democrats and Republicans resembles some of the biggest gaps in the American cultural landscape.

“We really disagree on a lot of education issues, and that trend has accelerated over the last decade,” he said. “The difference in positive evaluations of teachers unions is about the same size as the partisan gap on legal abortion in all circumstances.”

9/11’s Permanent Stamp on NCLB: Tragedy, Triumph, and Failure

If education politics has absorbed some of the acrimony surrounding other issues, this represents a break with historical patterns. Schools have traditionally been isolated from national trends by their unique governance structure, with elected boards attracting little public attention when deciding funding and curriculum issues. When presidents have joined the fray—as in the case of school desegregation in the 1950s, or the attempt to pass the No Child Left Behind law in the early 2000s—they have encountered resistance, but rarely failed completely .

Morgan Polikoff, a professor of education at the University of Southern California, agrees that the past decade has brought increased partisanship. Yet he also expressed hope that future presidents, including perhaps some who now hold state-level office, can achieve greater successes in education policy than Washington has recently seen.

I would imagine that there would again be national leaders who were charismatic and had strong views on the role of federal education policy. We just don’t have them right now, and we didn’t have them during the last administration.

Morgan Polikoff, University of Southern California

“I would imagine that there would again be national leaders who were charismatic and had strong views about the role of federal education policy,” Polikoff said. “We just don’t have them right now, and we didn’t have them during the last administration.”

The Obama Exception

To estimate the influence of high-profile politicians such as current and former presidents, Houston built his study on 2007 public opinion research.

The annual one Education next poll, developed and administered by Harvard researchers, is one of the few measures that regularly surveys the public about their attitudes toward education topics. The article draws on responses from five separate editions of the poll, including questions on topics such as school choice, teacher earnings and allowing illegal immigrants to be educated in the state to attend public universities. (Houston, which previously served as Education Next research director, has previously used similar data to show that overall opinions about schools become more partisan over time.)

What do Americans think about school choice? Depends on how you ask the question

“I’m looking at questions that have been asked in exactly the same way, or almost exactly the same way, over the course of at least a decade,” he said. “Regardless of the imperfections of the survey questions – and every survey question has imperfections – these hold true over time so we can capture trends.”

Before a random group of participants gave their own opinions on eighteen policy proposals, they were first prepared by hearing the sitting president’s opinion on them. Because respondents included Democrats, Republicans and independents, Houston was able to gauge their reaction when they heard that a highly visible figure from the same or opposing party had an opinion on a particular policy.

The overall result of receiving a partisan signal—effectively becoming aware of the president’s support, regardless of one’s own political leanings—was statistically insignificant, changing respondents’ attitudes by only 0.02 points on a five-point scale. But that average is responsible for larger effects that have moved Democrats and Republicans in opposite directions: if anyone were to teach a president that of his own party were in favor of a specific education policy, they were in favor of it by an average of 0.37 points. If a president from the opposite party was found to favor a policy, whether school vouchers or universal pre-K, the respondent deviated from that proposal by 0.32 points.

In other words, voters carefully weigh what high-profile figures like U.S. presidents say about schools. But their statements tend to be counterproductive because they divide the public along partisan lines.

Recent history provides some support for the article’s hypothesis. For example, multiple studies of school districts’ behavior during the pandemic have found that their local partisanship, far more than the prevalence of COVID in the area, was strongly linked to whether they heeded President Trump’s 2020 exhortation to close schools open for personal meetings. learning.

Research shows politics, not science, is reopening driving school decisions to a ‘really dangerous’ degree

Interestingly, one part of the results actually showed the opposite effect, bringing both parties slightly closer together. When a president supports a policy not traditionally associated with his party and its base — the prime example being Barack Obama, whose endorsement of charter schools, merit pay and higher academic standards was revealed to partisans in three separate polls — it actually depolarizes reactions : Democrats moved 0.28 points toward the previously unfavorable proposals, while Republicans moved 0.14 points in the opposite direction.

Charles Barone, the vice president of primary and secondary education policy for the pressure group Democrats for Education Reform, said his own observations of voters during the Obama era were largely consistent with the survey’s conclusions.

“Obama’s support for education reform, especially charter schools, has helped Democrats,” Barone said. “We saw higher polling numbers among Democrats on issues like charters after Obama came out.”

Elusive common ground

Education observers generally agreed that polarization around schools has markedly escalated since the Obama administration, and that many mainstream voters rely heavily on their party leaders for judgment on policy initiatives with which they are unfamiliar.

But while Polikoff agreed that the receding center posed a “major problem” for those trying to improve the way schools deliver education, he added that President Biden’s most recent predecessors may have been particularly good at exerting partisan energy.

“You wouldn’t necessarily want to extrapolate from these two presidents to all of them,” he said. “Obama and Trump were, if nothing else, highly visible and almost ubiquitous in a way that other presidents may not be — and that state and local leaders, who actually influence these policies — are not.”

State leadership may also offer some reason for optimism. While rancorous battles over school closures and controversial classroom materials have made headlines in recent years, long-awaited bipartisan support has also fueled efforts to integrate the science of reading into literacy education. And to further illustrate Houston’s findings, a slew of Republican governors have taken the opportunity to raise teacher salaries, winning popular approval in part by embracing a position usually associated with Democrats.

Why are so many Republicans raising teacher salaries?

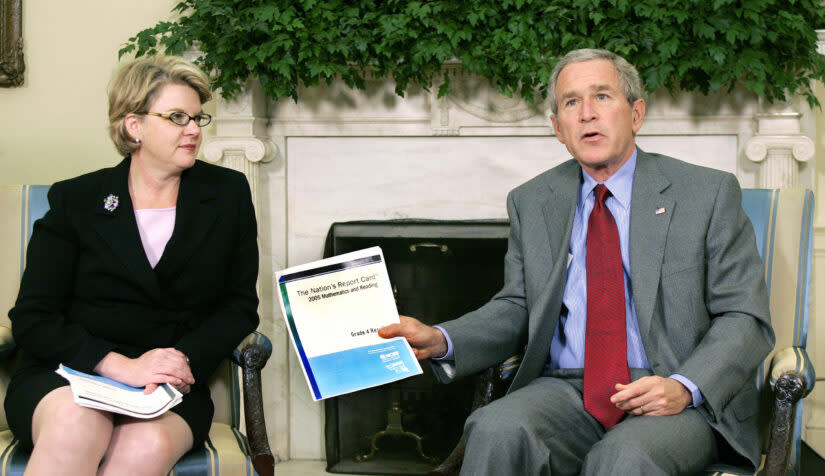

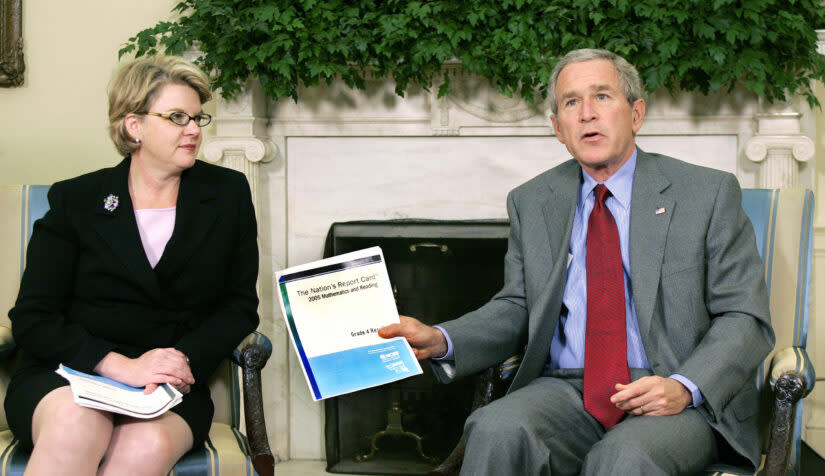

Margaret Spellings, formerly the U.S. Secretary of Education under President George W. Bush, is now CEO of the Washington-based Bipartisan Policy Center. An enthusiastic supporter of No Child Left Behind-style education reform, she said she was struck by the “vacuum of federal leadership and cohesion” now in Washington.

“I wish someone would tell me what the Biden K-12 policy is. There is no. And the Trump administration was all about vouchers.”

– Margaret Spellings, Bipartisan Policy Center

She said she still keeps memories in her office of the passage of the law, which was supported by huge margins in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. That happened during the administration of a much more unifying president — Bush had sky-high approval ratings in the wake of the September 11 attacks, and NCLB was seen as an important bipartisan compromise — but the victory reflected what political will and energy could be . achieve, she added

“I wish someone would tell me what the Biden policy is for K-12 education,” Spellings said. “There is none. And the Trump administration was all about vouchers. But I haven’t given up on bipartisanship, period, or I wouldn’t be doing the work that I do.”