The Federal Reserve’s roughly $1 trillion pile of paper losses stemming from its undersea securities holdings have begun to turn into actual losses of more than $100 billion, with no relief in sight.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said Wednesday that easing inflation is still not close enough to meeting the central bank’s 2% annual target to cut interest rates from 20-year highs.

Most read from MarketWatch

The longer interest rates remain high, the harder it will be for the Fed to repair its balance sheet. Importantly, restrictive interest rates could cost the Fed about $100 billion a year well into the next decade, said Ali Meli, chief investment officer of Monachil Capital Partners, a credit fund he founded in 2019.

Meli arrived at that estimate by poring over the Fed’s financial statements, which showed an unrealized loss of $948.4 billion at the end of 2023 on assets purchased on the open market, compared with more than $1 trillion in non- realized losses at the end of 2022.

How did the Fed get here? The central bank aggressively used its balance sheet during the 2007-2009 financial crisis and the 2020 market panic to gobble up bonds that would otherwise have been in the portfolios of asset managers, 401(k)s and other investment vehicles.

This helped stabilize shaky financial markets, but also came at a cost. Balance sheet expansion could also go too far, boosting demand for risky assets like stocks and crypto while fueling inflation, which hits wage earners the most.

Before striking out on his own, Meli spent 15 years at Goldman Sachs’ global structured finance group, where, among other things, he helped the bank establish a tactical short position in the housing market through monoline insurance companies before the 2008 collapse.

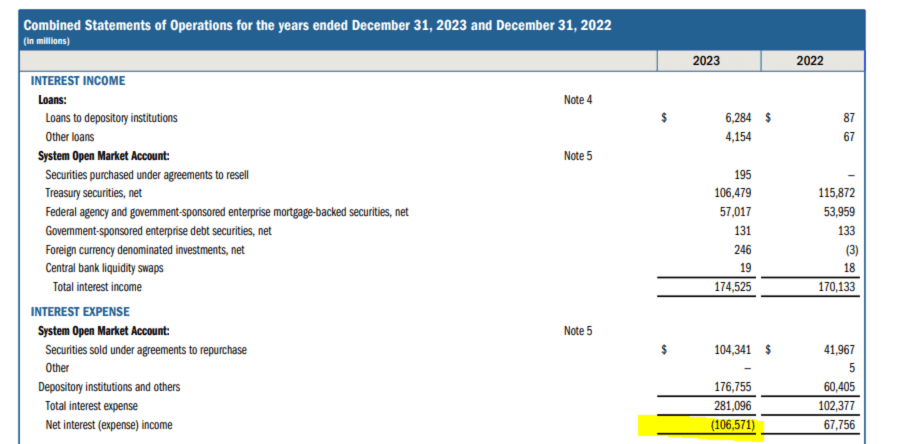

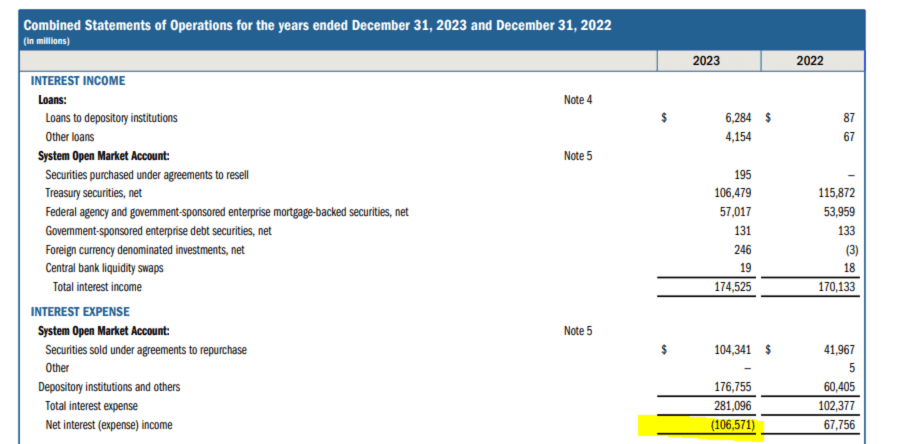

To gauge the cost of the Fed’s support during the pandemic, Meli tracked the central bank’s interest costs, which have risen since last year. Interest expense was positive at nearly $68 billion in 2022, but accounted for most of the $114.3 billion loss reported in March last year.

“The Fed saved Wall Street,” Meli said, pointing to the large amounts of 2% and 3% long-term Treasury and mortgage bonds the Fed has bought during the COVID crisis. Now it is under water because it also has to finance its activities at the current policy interest rate of 5.25 to 5.5 percent.

“If they had reduced their balance sheet before raising rates, they wouldn’t have had such big losses,” Meli said. “But maybe they shouldn’t have expanded it as much as they did in 2020.”

Tracking Fed Losses

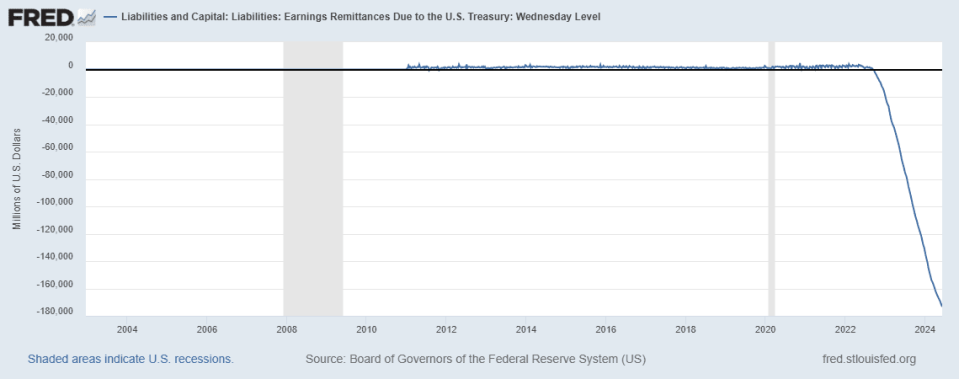

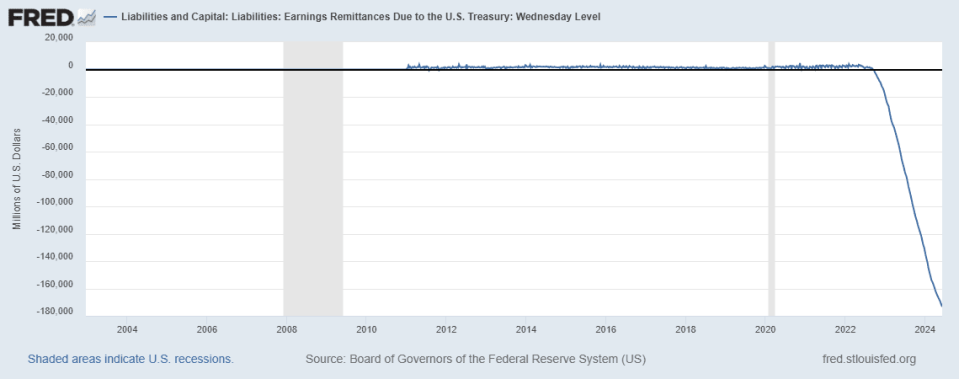

Since the Fed must return any profits it makes to the Treasury, another way to track its deficit is via this chart, which shows that remittances have recently turned negative — with the gap last seen at around $170 billion was estimated.

Lower rates could help restore some of the paper losses in the Fed’s portfolio.

“In terms of unrealized losses, that is not a major problem for the markets as long as the Fed’s solvency is not called into question,” said Danny Zaid, fixed income portfolio manager at TwentyFour Asset Management.

In a recent twist, Senator Mike Lee, a Republican from Utah, introduced a bill that would abolish the Federal Reserve, complementing a bill introduced by Kentucky Republican Thomas Massie in the House of Representatives.

Currently, unlike an underwater bank facing a run on its deposits, the Fed is in no danger of resorting to forced asset sales, which would crystallize losses.

Ultimately, the Fed may return to using its printing machine to cover its losses, Zaid noted. “I know the numbers sound big – and I think they will impact monetary policy and Fed action in the long run,” he said.

Zaid also thinks the Fed would step in again to support shaky markets if more instability were to occur, including at regional banks.

Related: Moody’s has downgraded several U.S. regional banks over commercial real estate concerns

“The issues, especially around commercial real estate and regional banks – that’s a problem that’s still there,” he said.

Election risks

The US central bank has shrunk its balance sheet from a peak of nearly $9 trillion by allowing a number of bonds to mature each month without reinvesting the proceeds. The process slowed from June, when the Fed tried to tighten financial conditions without causing a recession or shocks to the financial system.

In the past, the Fed made money from assets it bought to help stabilize the economy and financial markets. Older government bonds with higher yields became more valuable – and scarcer – when the central bank cut interest rates in 2007 as the global financial crisis spread, largely because interest rates were kept low for the next 15 years.

But the COVID era has played out very differently, with the Fed buying trillions of dollars of low-yield Treasury bonds and agency mortgage bonds that became worth less, not more, when the central bank raised rates.

Although many view the Fed’s expanded balance sheet as an inflationary force, it also strengthened the economy by keeping credit cheap and plentiful for businesses and households. Most homeowners refinanced 30-year mortgages with fixed rates less than 4%.

“I don’t think it matters until it matters,” said George Catrambone, head of Americas Trading and Fixed Income at DWS Group, of the Fed’s large and underwater balance sheet. “If you actually find that soft landing, that proves it was just enough.”

Forecasters still expect the Fed’s balance sheet to stabilize at around $7 trillion this cycle, to help ensure liquidity in financial markets.

But on days that bring more resilient U.S. economic data, investors tend to focus on higher interest rates, climbing debt service costs and increasing budget deficits, Catrambone said, noting the choppy backdrop for Treasury auctions over the past eighteen months. “The narrative boomerang returns to that.”

Catrambone also thinks potential political risks in the US linked to the November election may be underpriced, especially after French President Emmanuel Macron called for early elections in an attempt to thwart the rise of the country’s far-right party .

Should a “red wave” surface, allowing Republicans to capture both the White House and Congress, he sees risks that the Trump-era tax cuts will be extended, rather than disappearing as expected.

“That makes the budget picture more challenging,” said Catrambone.

Read the following: Cost of Trump tax cuts rises 50% amid ‘abuse’ of business loopholes

Greg Robb in Washington contributed reporting .