(Bloomberg) r More than two years after the Federal Reserve’s most aggressive monetary tightening in forty years, the big surprise is that the world has not collapsed.

Most read from Bloomberg

While U.S. yields are at their highest levels in 23 years causing pain, nothing like the systemic problems that so often wiped out expansions in the past. The Fed has kept its policy rate at 5.25% to 5.5% for about a year and is expected to leave it unchanged at its two-day policy meeting this week.

With a set of stable economic data ending Friday, investors have dialed back their expectations for rate cuts, with just one – or perhaps two – now expected by the end of the year.

The financial markets continue to digest Chairman Jerome Powell’s ‘restrictive’ policy very well. The three bankruptcies of US regional banks in the spring of 2023 are particularly notable for their limited impact on the economy and the speed with which regulators were able to halt any contagion. Credit spreads remain tight, even among riskier bonds, and volatility is low.

In other words, something different is going on this time, and it’s catching the attention of the Federal Open Market Committee — the Fed panel that sets interest rates — and they’ll likely bring up the topic of easy financial conditions again this week to take. Here’s a look at three unusual features that help explain why policies have less power:

Privatization of risk

When technology stocks started falling in 2000, and assets tied to subprime mortgages plummeted in 2007, it was there for all to see. As fear of losses spread, sales hit more and more assets, causing greater contagion and ultimately gripping the economy.

What is different today is that an increasing share of financing comes from private rather than public markets. Part of this is the result of stricter regulation of listed financial institutions. Pension funds, endowments, family offices, ultra-wealthy individuals and others are now more directly involved in non-bank lending than in the past.

Non-bank lenders have been mainly active with mid-sized companies, but they are also involved with large companies. There is an oft-quoted estimate of private credit totaling $1.7 trillion, but the lack of transparency means there is no precise official count.

Because this lending falls outside the visibility of the public markets, problems that do develop have less chance of contagion. Missed interest payments are not the subject of public news headlines, driving investors to herd behavior.

Pension funds and insurance companies investing in private credit funds are unlikely to ask for their money back tomorrow, reducing the risk of sudden stops in funding.

The caveat:

Just because nothing has led to a major explosion in this area yet doesn’t mean it won’t happen. A recent incident in which a company removed assets beyond the reach of its lenders – part of an effort to attract new financing – was an eye-opener for many on Wall Street.

The IMF devoted an entire chapter to private credit in their April financial stability report, and their assessment was mixed. The size and growth of the market mean that “the market could become macrocritical and amplify negative shocks,” the fund said. The pressure to close deals can lead to ‘lower underwriting standards’.

Fabio Natalucci, a deputy director at the fund overseeing the report, said in an interview that private credit’s “ecosystem is opaque and there are cross-border implications” if the market goes into a convulsion.

He worries about “layers of leverage” in the chain of investors, the funds and the companies they own.

Government debt drives growth

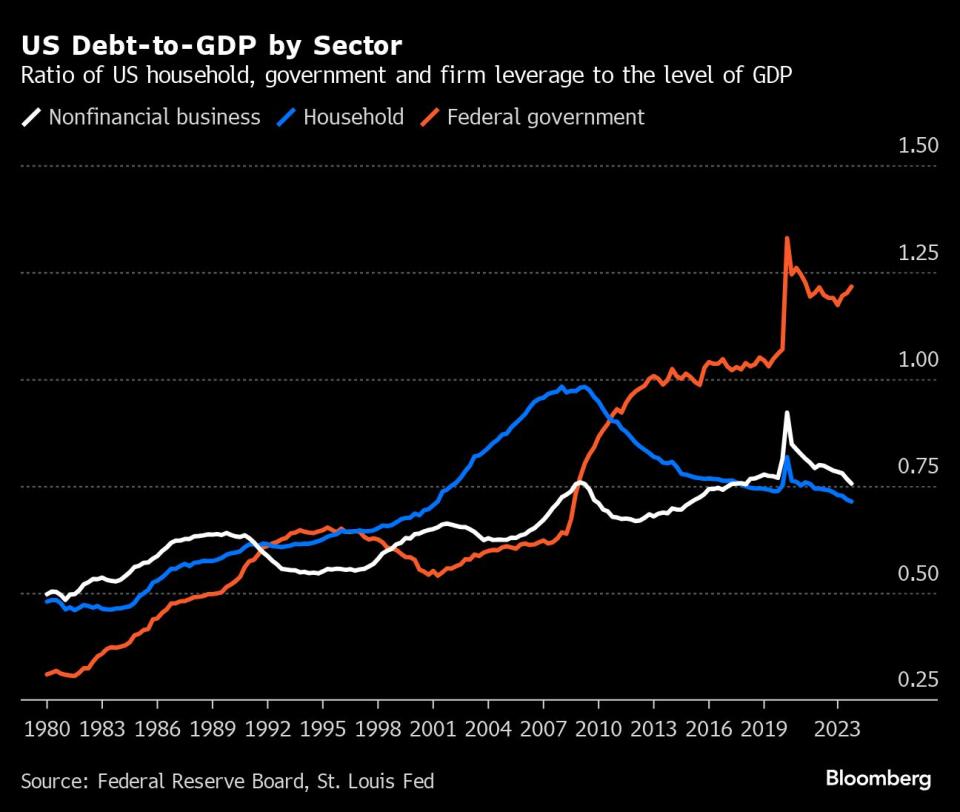

The 1990s expansion ended in a crash after companies overextended themselves, obsessed with dreams of dot-com riches. In the 2000s, it was households that used their own assets and borrowed against the expected increase in the equity of their home. This time it is the federal balance sheet that has played an unusually large role in the expansion.

Government spending and investments contributed the largest share of GDP growth in more than a decade in 2023, and of course they are financed by debt – which, according to the Congressional Budget Office, amounted to 99% of GDP in the 2024 fiscal year.

The graph below shows how dramatic the role reversal between households and the government has been:

Government debt is called a risk-free asset because it is safer than a household or business because federal authorities have the power to levy taxes. That means tapping the federal balance sheet for growth is inherently less dangerous than an increase in private sector lending.

The caveat:

Even governments can run into trouble, as Britain found in 2022 when investors resisted plans for large, unfunded tax cuts. Rising interest rates are increasing America’s borrowing needs, and warnings are emerging that the US is on an unsustainable fiscal path.

“There is almost certainly a limit to the amount of debt outstanding without the market pushing up yields,” said Seth Carpenter, chief economist at Morgan Stanley. But if there is a tipping point, it’s hard to believe we’re there now.

The Fed is balancing the risks

As the Fed has raised rates and shrunk its bond portfolio, Powell and his colleagues have been particularly alert to downside risks. The central bank stepped up with emergency funding when Silicon Valley Bank collapsed in March 2023, even as the bank struggled with inflation.

Powell and his lieutenants have also effectively dismissed further rate hikes, given the still strong economy and inflation still above policymakers’ target. There is even a strong preference for lowering borrowing costs, in a nod to trying to avoid acting too late and pushing the economy into recession.

The Fed’s communications help limit volatility and contribute to an easing of financial conditions in general. It appears strategic and deliberate on the part of the Fed, suggesting that Powell and his team are attuned to the powerful threat of the so-called financial accelerator, where a rise in unemployment or a drop in profits hits back on the markets and creates negative shocks strengthened, threatening a rapid crisis. fall into a recession.

The Fed is trying to keep its ‘tight’ monetary policy a few degrees below the boil. This has given rise to a paradox. Fed officials say their policies are restrictive, but financial conditions are still easy.

The caveat:

Fed policymakers cannot micromanage all aspects of the financial system and economy. There are real pain points and the risks are concentrated in areas with less visibility. High interest rates for a long period of time are starting to weigh on you.

“There’s a lot more stress behind the scenes,” said Jason Callan, head of structured investments at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. “The real pivot is the labor market.”

Much of the lending to low-income households is done by fintech companies, outside the scrutiny of regulators. The resilience of the shadow banking system and consumers in a recession without wage protections and stimulus checks remains to be seen.

“The more inequality, the more financial instability,” said Karen Petrou, co-founder of Federal Financial Analytics, a financial industry analytics firm, in a recent speech. “It is increasingly likely that even small amounts of macroeconomic or financial system stress can quickly become toxic.”

—With help from Laura Curtis.

Most read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 BloombergLP