Next week is the annual Opening of the Beaches. When some third-graders at Neptune Beach Elementary go to the beach, they might see it a little differently.

They won’t just see miles of sand.

They will see ancient mountains.

They will see gold and rubies.

They will see toothpaste and titanium.

They might even notice the white “S” on Skittles.

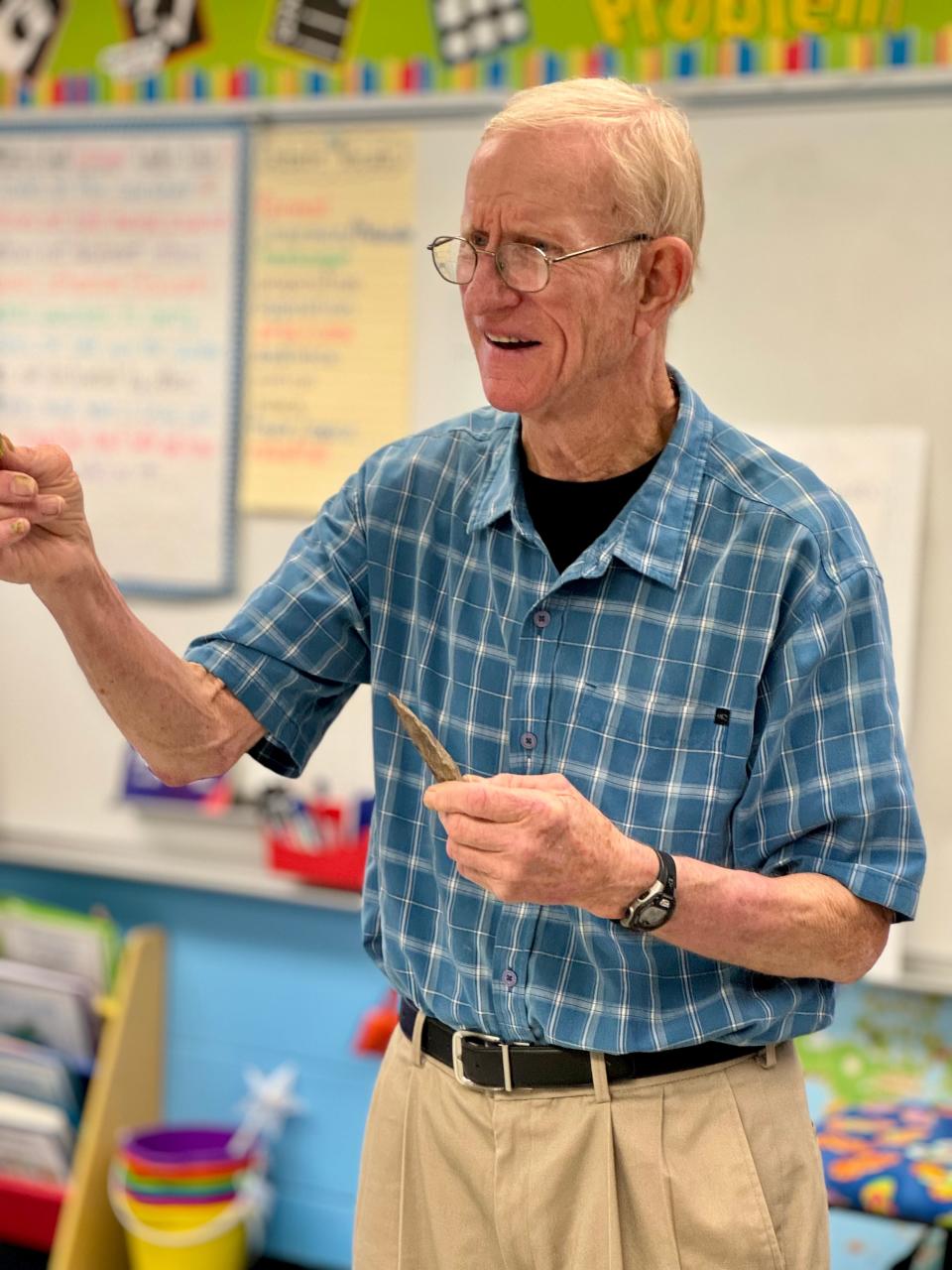

For example, Bill Longenecker recently started a program in Mrs. Peterson’s third grade class by handing out skittles.

“You can eat it if you want,” he said as he walked from table to table, handing each student a small package of the multi-colored candies. “But you don’t have to participate in this experiment. It’s all in the name of science.”

‘Retired Mountains’

It’s not just Neptune Beach’s third graders who will look at the beach a little differently.

There are hundreds, maybe even thousands, of kids in Jacksonville who might feel a little differently about our sand (and more), thanks to someone who, at 76, looks like a piece of the beaches.

Longenecker, who grew up on the beach, has been recording surf reports every day for 40 years. For decades he wrote freelance columns for the Beaches Leader and Shorelines. And although he has retired after 42 years as a paramedic, he has remained busy and involved. He volunteers twice a week in the ER at Beaches Baptist and goes to schools to talk to students about science.

“My goal is to help them understand that science surrounds us,” he said. “It’s not just something to remember for a test.”

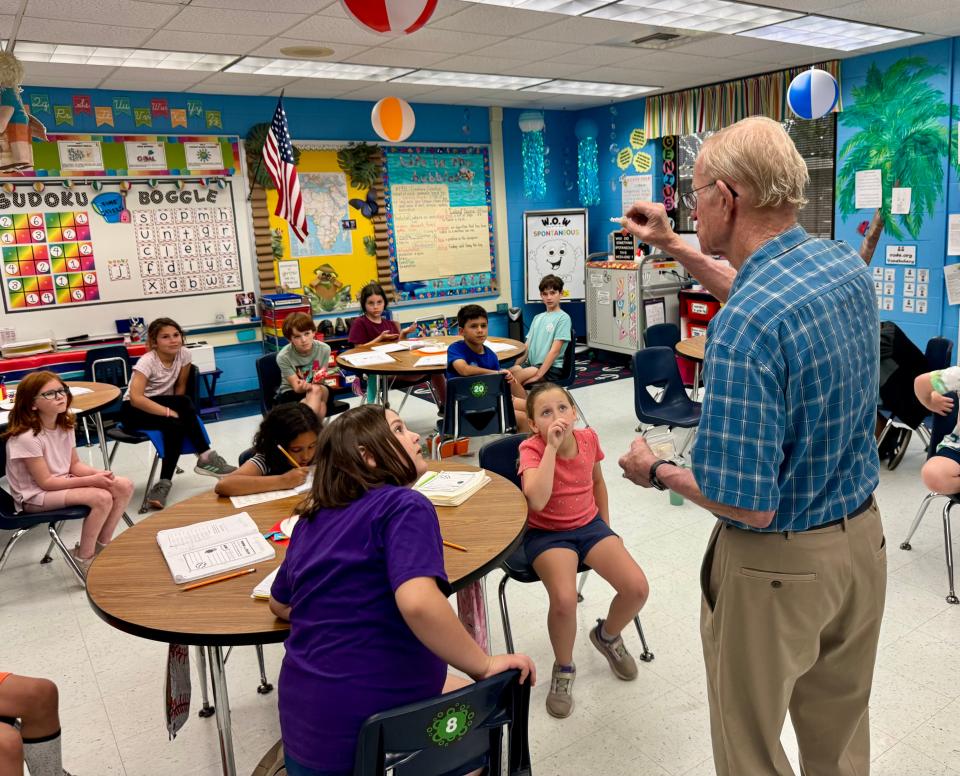

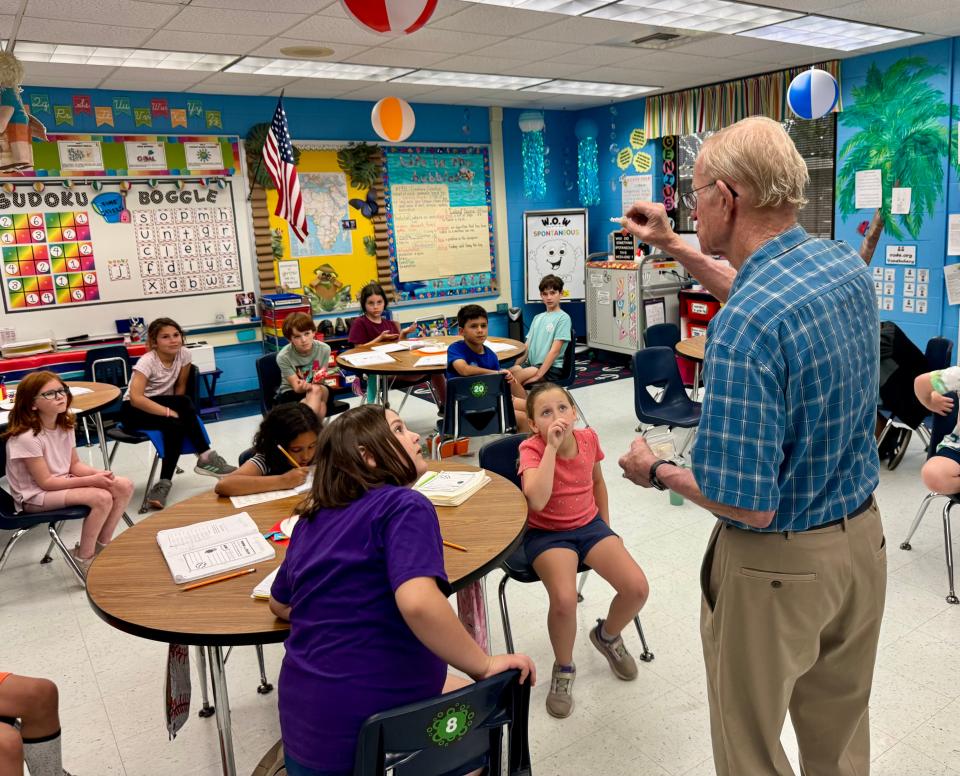

He has done his science programs – on everything from atoms to snakes to our hearts and brains – at about a dozen schools. But it seemed fitting to join him at Neptune Beach Elementary, a school where he has been teaching programs for more than a decade, teaching the program he has titled “Our Beaches: Retired Mountains.”

Gold on our beaches

He emptied a large container full of stuff. Smaller plastic containers full of rocks. A sheet of paper with mineral samples. A microscope. A flint arrowhead. A pearl necklace. Old pictures. Colgate toothpaste. Tums. Ajax cleaner. A bag of sand.

“Raise your hand if you’ve ever been to the beach,” he said, standing in the middle of the classroom with a bag of sand in his hand.

He asked the students if any of them had ever eaten beach sand, not by accident, but because they wanted to. Some raised their hands. One girl said: “That’s disgusting.”

“Okay, how many of you just ate a skittle?” he said.

Hands shot up.

“Congratulations,” he said, holding up a small pebble. “You just ate something that has this beautiful rock in it called rutile, titanium dioxide.”

He explained that it is in all kinds of household items and foods, from sunscreen to skittles. And then he described one of the places you might find rutile, as the heavy mineral in beach sand.

“Have you ever walked on the beach and noticed that there are different colors of sand?” he said. “Especially after a nor’easter there are long strips of dark sand. People used to think that was pollution. Where do our beaches come from?”

A boy replied: rocks that used to be huge boulders?

“Good,” Longenecker said. “And where were those huge boulders?”

He asked if they had ever been to the mountains of Georgia, Virginia and North Carolina. He explained that about 20,000 years ago, when the last ice age ended, it scraped the mountains into what they are today and washed dozens of minerals to the coastline.

“You can even find gold on our beaches,” he said.

He asked if anyone had a large paperclip. One of the students found one for him. He held it up and said that if it was solid gold, it could sell for $50 to $75 depending on the day.

“That’s how much gold there is on our beach,” he said. “If I broke it up into thousands of pieces and spread it from one end of Neptune Beach all the way to Jacksonville Beach, you would never find enough of it to make any money.”

A billion years old

But the dark sand does contain minerals, such as rutile, that have led to mining in the past. Ponte Vedra was once known as Mineral City. And when Longenecker’s family moved to Northeast Florida in the early 1950s, he remembers seeing enormous white sand dunes behind Regency Square.

Longenecker, who was an avid runner and cyclist for decades, held up a piece of a bicycle frame, a titanium tube. He explained that this metal was chosen because it is resistant to corrosion from the elements. Then he tapped one of his knees.

“I have an artificial knee and part of it is made of titanium – not necessarily of us sand, but beach sand,” he said.

He held up another stone and asked, “Where is the nearest limestone?”

One of the boys gravely gave an answer that was hard to dispute.

“In your hand?”

Longenecker laughed. He said that was a great answer, but not exactly the answer he was looking for. He explained that about 25 to 50 feet deep, you can find the backbone of Florida: calcium carbonate and limestone.

He asked the students if any of their parents had ever said something like, “I’ve told you to clean your room a million times?”

“That’s a bit of an exaggeration,” he said. “But this is not an exaggeration. Another mineral on the beach is zircon. … The rock I’m about to pass on could be a billion years old. Everyone uses these big numbers and no one thinks about them much. So let’s do a little math.”

He asked the students to snap their fingers once per second. He asked them how many times they would break them in a minute and then in an hour.

“If you wanted to snap your fingers a million times, once every second, it would take 12 days, counting day and night,” he said. “Can you guess how long it would take to reach a billion?”

After a few guesses, all far too low, he gave the answer: almost 32 years.

“This rock could be a billion years old,” he said. “And yet it is part of the sand on our beach.”

He set up a microscope so that the students could look at grains of sand. One girl, Avery, was so excited by what she saw that she kept insisting that I should watch too.

Longenecker told the children about quartz. He explained lithification. He showed them pressed sand called mudstone that came from Hanna Park and contained the backbone of a whale in it. He showed them a small tubular fulgurite and said this is what can happen when lightning strikes sand.

And finally, at the end of his presentation, he introduced another kind of fossil, a newspaper columnist, and asked if any of the young students had heard of newspapers.

“My grandpa has one,” said one girl.

I asked the children to go around the room and share what they found interesting. Emma pointed out that zircon is a billion years old. Makenzie said the gold and rubies on the beach. Brandon talked about Longenecker showing how to rub two pieces of flint together to make sparks. And Grady went back to the beginning of the program.

“There’s some kind of rock in candy, toothpaste and more – mind-boggling,” he said. “And it kind of ruins Skittles for me, too.”

mwoods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared in the Florida Times-Union: Longenecker wants Jacksonville students to appreciate science and beaches